Trump and Greenland – A Legal Paradox

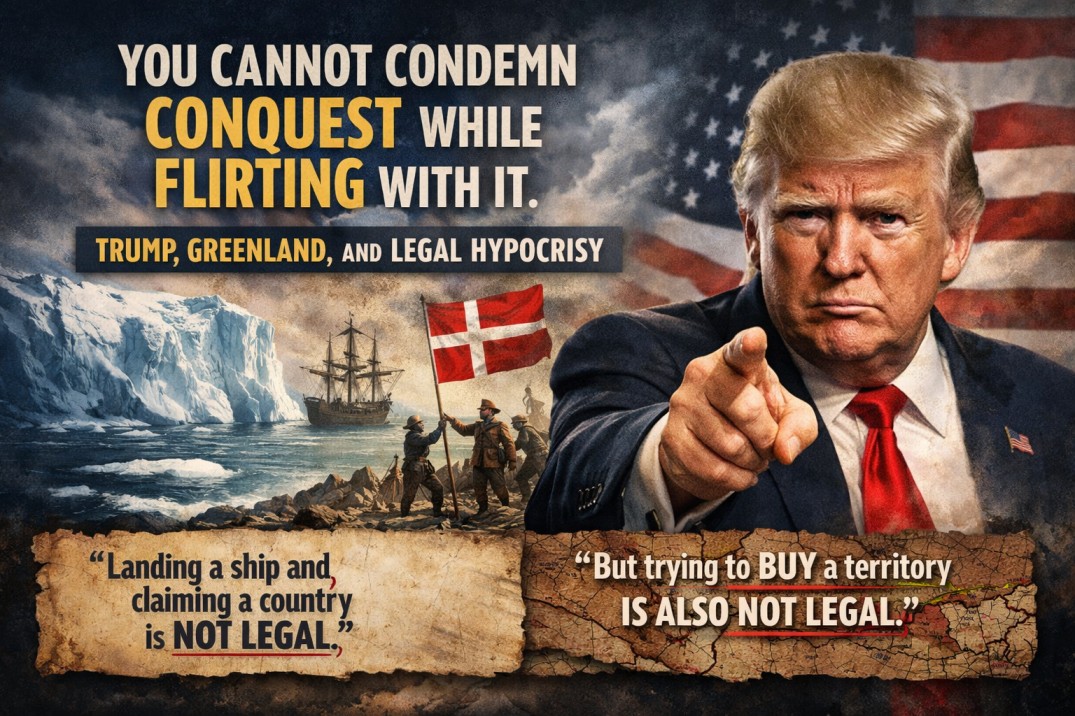

When Donald Trump declared that landing a ship and claiming a country is not legal, he was stating an uncontroversial truth. That principle has been settled in international law for decades. What makes the statement remarkable is not its accuracy, but Trump’s failure to apply it consistently, particularly in relation to Greenland.

Modern international law rejects territorial acquisition by discovery, force, or symbolic acts. The colonial age of planting flags and declaring ownership ended in the twentieth century. Sovereignty today rests on recognised title, effective governance, and the right of peoples to self determination. Greenland meets all of these criteria as an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark. Its status is neither disputed nor provisional.

Yet Trump’s repeated expressions of interest in acquiring Greenland, sometimes framed as a purchase and sometimes as a strategic necessity, undermine the very principle he claims to defend. Suggesting that territory can be transferred through economic leverage or political pressure is not meaningfully different from the older logic of conquest. The method is softer, but the assumption is the same. Powerful states decide. Smaller peoples are expected to comply.

History offers uncomfortable parallels. Nineteenth century imperial powers often justified territorial expansion not through overt warfare, but through treaties signed under pressure, financial inducements, or strategic coercion. These arrangements were later condemned precisely because consent obtained in the shadow of power is not genuine consent. The law evolved to close this door. Trump’s Greenland rhetoric attempts to reopen it.

The hypocrisy is sharpened when viewed against the United States’ own legal positions elsewhere. Washington rightly condemns unlawful territorial claims when made by rivals. It insists that borders cannot be changed by force or unilateral assertion. These arguments rely on a stable international legal order. That same order, however, is treated as negotiable when strategic advantage points northward to the Arctic.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Denmark’s sovereignty over Greenland gives rise to exclusive rights over surrounding maritime zones and seabed resources. Military presence or strategic interest does not alter this. The law is clear. What is unclear is why it should apply only when convenient.

Opinion matters here because international law is not self enforcing. It survives through consistent respect, especially by powerful states. When leaders selectively invoke legality, they weaken the rules they rely on to restrain others. Trump’s position suggests that conquest is illegal only when it is crude, visible, or undertaken by someone else.

Trump was right about one thing. Landing a ship and claiming a country is not legal. But neither is attempting to acquire territory through economic pressure, political bargaining, or casual disregard for the will of its people. Sovereignty is not a commercial asset. Greenland is not a strategic bargaining chip. And international law does not change simply because a powerful state finds it inconvenient.